My Blogs

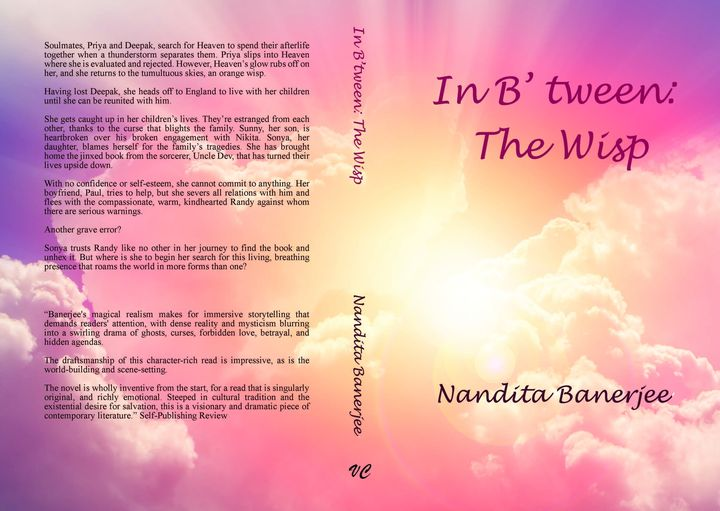

My newest book, In B’tween: The 3 Claps of Thunder is out now.

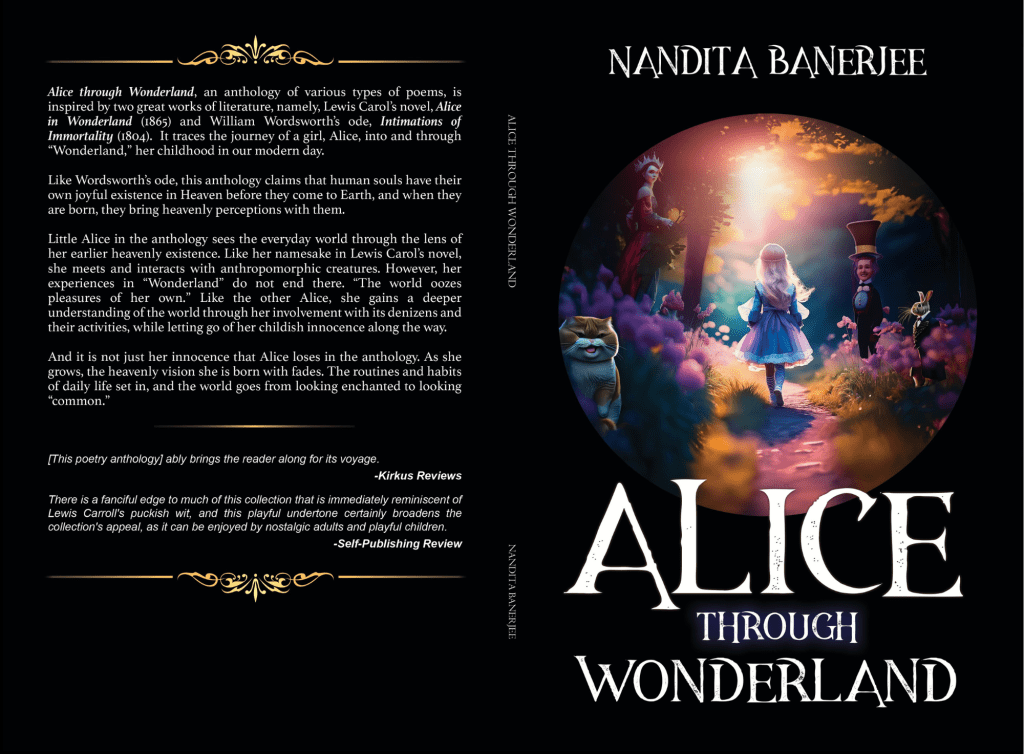

About “Alice Through Wonderland”

Alice Through Wonderland is out on Amazon today

Available at https://a.co/d/hQMgqNv

KIRKUS EDITORIAL: Alice Through Wonderland

Hello Nandita,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript for a collaborative edit. It’s not often that I get to apply a more academic or literary lens to an editing assignment, so this project was truly a treat for me. Normally I wouldn’t divulge too much of my own academic background, but in the case of this edit, perhaps it could give my feedback some context. I’ve studied British Victorian literature in the past, including both undergraduate and graduate school, and I’m deeply familiar with Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Of course, given that the English Romantic movement formed the bedrock for British literature later in the nineteenth century, I’ve also studied that movement to some extent (though not to the same extent as I have German Romanticism, which is the fate of anyone who finds that Goethe really speaks to them while in their early twenties). Again, I say all this because I have a decent amount of familiarity with the subject matter, and I get the impression you are targeting readers who also have some familiarity with these movements and writers. Your author survey requests feedback around how Wordsworth’s “Ode to Immortality” and Alice come through the collection and mesh, and my hope is that this letter can provide you with some insight.

First, I should mention that I used a light hand during my line edit of your collection. This is because you clearly have mastered the craft of writing, so I didn’t need to make many corrections or call out glaring mistakes. I left a few comments throughout describing what changes I did make, along with a few small suggestions to tweak wording. It’s definitely the right move for you to be seeking more high-concept feedback, since I have no doubt that you can draft and execute a poem with practiced grace.

The choice to write a collection grounded in both Wordsworth’s “Ode” and Alice is such a unique angle and one that I personally find fascinating. Readers familiar with both writers will definitely see the influence throughout the collection, especially the echo of Alice, which, because of a plethora of adaptations, is so prevalent in the Western cultural consciousness.

One aspect of the collection I wanted to mention is the overall “direction” of the speaker. Wordsworth’s “Ode” is about a speaker who yearns for a lost childhood while observing the natural world. It’s a poem imbued with so much nostalgia for a bygone era: “Where is it now, the glory and the dream?” For Wordsworth, who looks back upon the “immortal sea,” the poem is from the perspective of an adult who seeks to regain what was lost in childhood. It’s written in the present tense, but it still features a speaker who is concerned with looking backward. Meanwhile, in Alice, Alice is a child throughout, as it’s only a single afternoon that passes her by—written by Carroll in past tense. Most of your collection is written in the present tense, giving it a sense of immediacy rather than the sense of a wistful yearning. The child in your collection is actively experiencing the slipping away of the divine sense that Wordsworth cherishes. I can track this departure from childhood wonder as the collection progresses, which captures the thrust of Wordsworth’s “Ode.”

As your collection progresses, the speaker seeks to apply sense and order to the world. I’m reminded of poor Alice as she attempts to apply rules of etiquette to Wonderland, accusing the wild and unexpected characters she meets as being rude or senseless. Your poems “A Puzzling Question” and “Tea Party Gone Mad” share this sense of frustration at attempting to apply order to chaos. Interestingly, it’s the other children in the poems who are the source of chaos, who ostensibly are the speaker’s equals (assuming they are all the same age, unlike Big Sis). In Wordsworth’s “Ode,” the speaker is concerned both with the abstract concept of childhood, not with the machinations of how children regard one another or reflect existing social hierarchies or customs. I’m glad you expanded your treatment of childhood to also feature groups of children.

One thing that I want to point out is how I was taken by surprise when I read the reference to Facebook toward the end of the collection. I suppose I assumed that the collection wasn’t grounded in a specific time. With regard to “Ode” and Alice, both capture very different perspectives of childhood that are deeply grounded in their time periods. I wonder if there are opportunities for you to impart a “modern” perspective on childhood within the collection? For example, Wordsworth’s poem is heavily grounded in the Romantic notion of divinity in the natural world and how it follows that children, before they learn “reason,” are part of that perfect system. Alice was published in 1865, just a few years before public education was introduced to children in Britain, and over the next few decades, the concept of childhood as a period of innocence began to take hold, with school helping to protect children from labor (in theory). But what does the childhood of 2024 look like? How do our contemporary cultural attitudes inform how we talk about children and how we think about our own childhoods? Your poem “Everyone is Mad Here” goes in that direction, by casting children as always being watched and judged even by strangers, but I’d like to see concepts like that taken further. In “Abundant Recompense,” the speaker describes his or her attention being taken by media, but I wonder if there’s something to be said about how in the twenty-first century, many children are from the time of their birth given avenues for distraction and consumption. Perhaps it’s low-hanging fruit to shake one’s fist at the “kids of today,” but in the spirit of crafting a narrative of childhood, I think it’s at least worth thinking about.

. . .

I personally love the “tail” poem! Calligrams are so fun. I understand your concerns about how the poem might be shifted around on mobile devices. Unfortunately, the adjustability of text could result in the shape being changed (e.g., if someone reading on a phone or iPad has low vision and makes the text bigger). My recommendation is the keep the poem as-is, because the individual lines are still short enough that the text would have to be VERY magnified to mess up the shape.

Again, I had a delightful time reading your collection and organizing some of my thoughts around the concept of the journey of childhood—both its genesis and its destination.

I look forward to discussing this project with you further.

A CALL FROM THE CRIME DEPARTMENT

After my press interview in Kolkata earlier this year about my newest book, In B’tween: the Wisp, the novel found some very interesting readers. The crime department of Kolkata grabbed it and after reading it through, thoroughly, they called me to inquire about one of the characters—Uncle Dev, the black magician.

If you have already read the book, you will recall not only Uncle Dev’s use of black magic to jinx the lives of my protagonist’s family, but also the paper plate of sliced fruit around a clay pot left outside a home to curse its owner.

Apparently, the crime department of Kolkata had encountered jinxed items I described in the book, not only in isolated alleyways but also in residential areas, and were interested in tracking the perpetrators.

“Is he real?” they asked. “How well do you know him? Could you please inform us about his whereabouts?”

“Me know a tantric?” I cried. “I have always been terrified of those sadhus.”

For nearly an hour, I tried to convince them that Uncle Dev was nothing more than a construct of my imagination.

“But he seems so real,” they insisted.

“Well,” I explained, “I grew up parallel to the Tantra society, in ignorance of their real aims, and in awe of their quirky clothes and facial makeup. Quite early on in my childhood, I witnessed some gruesome rituals tantrik practitioners use to hook people for their advantage. That sparked an interest in them, their lifestyle and their practices. There was this negative energy about them all the time. Something inexplicable.

“I know it’s all about being ignorant about a clan, but seeing is believing. Before I knew it, I had developed very strong feelings about them. Being a vivid dreamer, always intrigued by human behavior, especially strange and mysterious, I couldn’t help but write about them.”

The crime department asked no more questions.

Press Interview and Book Launch of In B’tween: The Wisp in Kolkata

My Latest Book